Updated: 8.3.24

When it comes to posture and back health, pro cyclists aren't the best role models. That's because low back and knee pain are the most common overuse injuries they experience (3,4). Despite having access to the most expensive and technologically advanced bike fitting tools, restrictive saddle tilt rules set by the UCI, and deeply rooted cycling culture norms were mostly to blame. Fortunately, in 2015, four years after I originally created this post, the UCI loosened the saddle rules, allowing time trialists to position the nose down by 10 degrees. Unfortunately, cycling culture norms and many bike fitters continue to push riders into a level saddle, even if they intend to ride aerodynamically. This forces riders into a rounded posture rather than a neutral posture, which is a known compensation pattern for those experiencing chronic low back pain. If you want to ride as aerodynamically as possible without compromising the lower back, it's important to know what a neutral spine is.

NEUTRAL SPINE DEFINED

NEUTRAL SPINE DEFINEDGood posture means having the two types of normal curves in the spine, lordosis and kyphosis. When the spine has a healthy amount of these curves, it can efficiently manage the forces of gravity, additional weight, and shocks. A healthy curvature will also allow the core muscles to rest at a length conducive to producing maximal force (2). Increasing or decreasing the curvature of the spine also lengthens and shortens the muscles of the core, making stabilization difficult in this imbalanced condition (1,2,3,4,5). If the core fails to stabilize, the repetitive flexion may lead to herniation of the intervertebral disks (5).

HOW TO DETERMINE NEUTRAL SPINE

While standing with the core relaxed, apply pressure into the core by driving the thumbs into the posterior side and the remaining fingers into the anterior and lateral sides of the core. This will help detect activation of the core. Slowly and incrementally adjust pelvic tilt anteriorly, then posteriorly to find the position which allows the core to uniformly disengage (relaxed), and uniformly engage with the belly button pulled in. This is your neutral spine. It takes practice to consistently remain in this position on and off the bike.

NEUTRAL SPINE ≠ ANTERIOR PELVIC TILT

A common misconception in cycling is that the pelvis must anteriorly tilt to maintain neutral spine. This has caused many to believe that a neutral spine will lead to the same low back issues related to an anterior pelvic tilt.

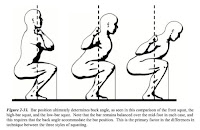

The best way to break this misconception is to look at the motion of the kettlebell swing and squat, and consider the motion of the pelvis relative to the torso.

When the posture at the start of the lift matches the posture at the bottom of the lift, this indicates no motion at the pelvis; rather, the pelvis tracked with the trunk to maintain the same curvature. However, if the lumbar spine or low back rounds at the bottom of the lift, then the pelvis tilted posteriorly. This is commonly known as "butt wink." If the lumbar spine actively extends at the bottom of the lift, then the pelvis tilted anteriorly.

Next time you ride, pay attention to how your back responds to different riding postures. If you can maintain a neutral spine on the hoods or tops, but experience rounding in an aero position, your pelvis posteriorly tilted. If the low back moves into more extension, then the pelvis anteriorly tilted. The goal is to maintain neutral spine on the hoods or tops, and in the aero position. This means your pelvis experienced no tilting; it maintained the same position relative to the spine. This is the outcome to aim for.

SADDLE SHAPE & TILT:

A saddle with a nose must be tilted down 10-15 degrees to give the pelvis enough room to follow the tilt of the trunk (1,2,4). Otherwise, the nose will create a physical blockade, forcing the pelvis to posteriorly tilt and round the low back.

A saddle with a nose must be tilted down 10-15 degrees to give the pelvis enough room to follow the tilt of the trunk (1,2,4). Otherwise, the nose will create a physical blockade, forcing the pelvis to posteriorly tilt and round the low back.

If it's possible to find a width compatible with your sit bones, noseless saddles provide huge advantages because they do not require nearly as much, or any nose down tilt. Without the nose, the torso can even tilt below horizontal while remaining fully supported on the saddle. It will take a long time until cycling culture fully accepts noseless saddles, but the demand is sorely needed to create more successful matches.

SADDLE HEIGHT:

Flexibility and mobility will ultimately determine saddle height. Cyclists with poor hamstring flexibility will have a flexed or rounded back if the seat is set too high. This will continue beyond 15 degrees of nose-down tilt.

SADDLE HEIGHT:

Flexibility and mobility will ultimately determine saddle height. Cyclists with poor hamstring flexibility will have a flexed or rounded back if the seat is set too high. This will continue beyond 15 degrees of nose-down tilt.

In severe cases where the saddle must be set too low to protect the spine, working on mobility and flexibility should be the top priority. As mobility and flexibility improves, reward yourself and your knees by raising the saddle little to utilize the newly acquired range of motion.

SUMMARY:

A neutral spine absorbs shock more efficiently and allows the muscles of the core to function normally. For those already suffering from lower back pain, 10-15 degrees nose down tilt was enough to bring the spine back into neutral and reduced the incidence and magnitude of low back pain in 80 cyclists (1,2,4).

A neutral spine absorbs shock more efficiently and allows the muscles of the core to function normally. For those already suffering from lower back pain, 10-15 degrees nose down tilt was enough to bring the spine back into neutral and reduced the incidence and magnitude of low back pain in 80 cyclists (1,2,4).

Resources:

- de Vey Mestdagh K. Personal perspective: In search of an optimum cycling posture. Applied Ergonomics 1998; 29; 325-334.

- Floyd, R. T.. Manual of structural kinesiology. 17th ed. Boston: Mcgraw-Hill Higher Education, 2009. Print.

- Mandy, Marsden, MPhil Sports Physiotherapy, and Schwellnus Martin. "Lower back pain in cyclists: A review of epidemiology, pathomechanics and risk factors." International SportMed Journal 11 (2010): 216-225. Print.

- Salai M, Brosh T, Blankstein A, et al. Effect of changing the saddle angle on the incidence of low back pain in recreational bycyclists. Br.J.Sports Med 1999;33: 398-400.

- Callaghan, J.P., and McGill, S.M. (2001) Intervertebral disc herniation: Studies on a porcine model exposed to highly repetitive flexion/extension motion with compressive force. Clinical Biomechanics, 16(1): 28-37

- Van Hoof, Wannes, et al. “Comparing Lower Lumbar Kinematics in Cyclists with Low Back Pain (Flexion Pattern) versus Asymptomatic Controls – Field Study Using a Wireless Posture Monitoring System.” Manual Therapy, vol. 17, no. 4, Aug. 2012, pp. 312–317, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.02.012.